I had the pleasure of hearing Mr. Lockwood play just once, at Fat Fish Blue. He was a warm, friendly person whose music came from the depths of his soul.

From today's Plain Dealer:

Lockwood attributed his longevity in part to exercising regularly, a habit he picked up as a teenage boxer. He said he did 30 push-ups and 30 knee-bends a day - most days, anyway.

He also had a low-stress outlook on life.

"I know I'm lucky," he told The Plain Dealer a few weeks shy of his 90th birthday. "I just try not to worry about nothing. Why do that?"

Words to live by.

Peace be with you.

YouTube of Lockwood playing "Sweet Home Chicago"

Robert Lockwood Jr., Cleveland's great bluesman, dies at 91

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

John Soeder

Plain Dealer Pop Music Critic

Grammy Award-nominated bluesman Robert Lockwood Jr., one of the last direct links to the primal blues of the Mississippi Delta and a popular fixture on Cleveland's music scene for decades, died of respiratory failure Tuesday afternoon at University Hospitals Case Medical Center. He was 91.

The singer-guitarist had been in the hospital since he suffered a stroke Nov. 3.

Lockwood "was a giant of American musicians," said his friend Nick Amster. "He was extremely influential."

Lockwood was born in Turkey Scratch, Ark. He moved to Cleveland in 1960.

When he was 11, Lockwood began taking guitar lessons from legendary blues pioneer Robert Johnson, a drifter who briefly moved in with Lockwood's mother.

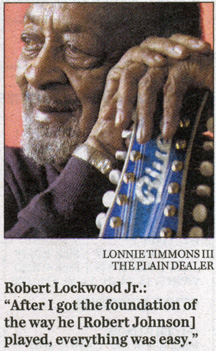

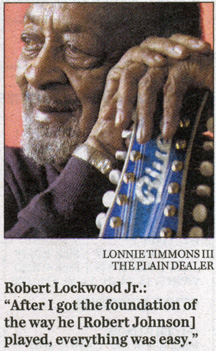

"He never showed me nothing two times," Lockwood said in a 2005 interview. "After I got the foundation of the way he played, everything was easy."

Lockwood honed his chops on street corners and in juke joints.

He later became a musical mentor to B.B. King, who used to listen to Lockwood in the 1940s on the "King Biscuit Time" radio show broadcast out of Helena, Ark.

Lockwood relocated to Chicago in the 1950s, where he was a sought-after session musician for Chess Records. He recorded with Little Walter, Sunnyland Slim, Roosevelt Sykes and other blues musicians.

Lockwood developed his own sound, going beyond the Mississippi Delta style he learned from Johnson to embrace jump blues, jazz and even funk.

For years, Lockwood had a weekly gig at Fat Fish Blue in Cleveland. On any given Wednesday night, you could find him presiding over the bandstand, a distinguished gentleman in a sharp suit. He coaxed grand chords and gritty leads from a 12-string electric guitar and drew upon hard-earned experience when he sang.

"I've been through so much - I don't give a [expletive]," he once told Benny Mostella, a trumpet player who backed the bluesman.

Lockwood was like a father to members of his band, some of whom had played with him since the 1970s.

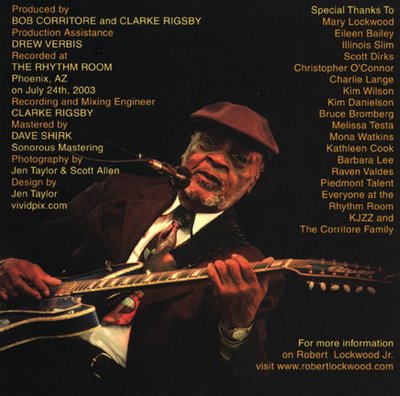

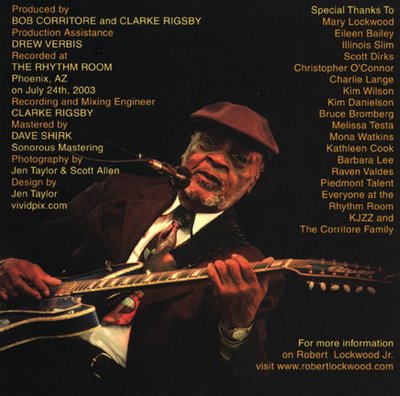

As a solo artist, he had a sporadic recording career, although his work did not go unnoticed. He earned Grammy nominations for two albums: 1998's "I Got to Find Me a Woman" and 2000's "Delta Crossroads."

When the latter CD lost to a collaboration between Eric Clapton and King in the best-traditional-blues-album category, Lockwood declared: "You know damn well my album is more traditional than theirs."

He had a way of making such prickly pronouncements as if he were merely stating the facts, not bragging. The more you hung around Lockwood, the more endearing his unfiltered candor and disdain for false modesty became.

On the piano in his Hough home, he kept a photo of Hillary Rodham Clinton - "Miss Hillary," Lockwood called her - presenting him with a National Heritage Fellowship in 1995.

"It's about time," Lockwood said when he accepted the prize, or so the story goes.

He toured throughout the United States, Europe and Japan. In July, he performed at blues festivals in England and Finland, accompanied by his longtime bassist, Gene Schwartz.

The Memphis-based Blues Foundation bestowed two National Blues Music Awards and four W.C. Handy Awards upon Lockwood and inducted him into the Blues Hall of Fame.

He received honorary doctorates from Case Western Reserve and Cleveland State universities. A street on the east bank of Cleveland's Flats was named in his honor in 1998.

At Fat Fish Blue, a bottle of Hennessy cognac with Lockwood's name on it was kept behind the bar. The restaurant also christened an entree after him: Robert Jr.'s Hennessy Cream Shrimp.

He and his wife, Mary, who survives, were married in 2000.

When Lockwood turned 90 in March 2005, the festivities included concerts at Fat Fish Blue and the Savannah Bar & Grille in Westlake. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum hosted a sold-out tribute, too.

He recently returned to the studio to appear on "The Way Things Go," the latest album by Cleveland Fats, aka Mark Hahn.

Lockwood attributed his longevity in part to exercising regularly, a habit he picked up as a teenage boxer. He said he did 30 push-ups and 30 knee-bends a day - most days, anyway.

He also had a low-stress outlook on life.

"I know I'm lucky," he told The Plain Dealer a few weeks shy of his 90th birthday. "I just try not to worry about nothing. Why do that?"